In this first installment of Blue Dot Writing’s Anatomy of a Scientific Paper series, we focus on how to choose a title for a scientific research paper.

The title is a reader’s first introduction to your paper. The title should be long enough to provide a specific and concise summary of the main thesis of the paper, but should be short enough that you don’t lose the reader. A maximum of 16 words is recommended. However, don’t rely on abbreviations to make the title shorter. Unless they are very commonly known, abbreviations should only be used in the main body of the text after the full term has been used, followed by the abbreviation in parentheses.

Focus on the Main Thesis

When deciding on a title, it is important to focus only on the primary thesis of the paper. Ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the number one thing you want people to take away from your research?

- What sets your research apart from previous studies?

- What is your most significant conclusion?

- What was the main question you sought to answer when performing the research?

- What was your primary motivation for pursuing this research?

Naturally, your paper will contain supporting information, especially in the introduction and methods sections. You may include interesting observations or secondary conclusions that arose during the research process that are important, but not directly related to your primary research question or goal. Those things are worthy of being included (in fact, they are vital to the scientific method), but you don’t need to mention them in your title.

Take this paper, for example: “The potential role of scavengers in spreading African swine fever among wild boar.” The paper talks about other topics not included in the title (e.g., carcass detection rate by birds vs. mammals, factors that influence the number of visits to a carcass by scavengers), but the title focuses on the primary thesis of the paper. The authors’ ultimate research goal was to determine “whether scavengers need to be considered as potential mechanical vectors for [African swine fever virus (ASFV)] within wild boar populations.” The focused title helps to inform the reader about the purpose and significance of the study.

Use Key Words

The title is one of the primary tools a potential reader will use to find your paper. The title should contain any vital key words that someone would likely use to search for information related to the study. This ensures that the paper will show up in relevant search results. Think about the words you would use to search for information on your research topic. Then, think about the words you would use to narrow that search to find your specific research on that topic. For example, if you wanted to know how marine mammals can dive so deep and for so long, you might use key words like “diving” and “mammals.” If you wanted to know more specifically how marine mammals alter their swimming strategies to help conserve energy during dives, you might use key words like “energetic efficiency” or “energy conservation” and “swimming strategies.” This would likely lead you to the paper by Terrie Williams titled, “Intermittent swimming by mammals: a strategy for increasing energetic efficiency during diving.”

Use Descriptive Phrases

Notice that the above title uses descriptive phrases instead of a complete sentence. The complete sentence version of this title might be, “Mammals use an intermittent swimming strategy to increase energetic efficiency during diving.” The difference is subtle, and both titles use the same number of words. Yet, the published title of the paper places the emphasis on the main focus of the paper: the discovery of the intermittent swimming strategy. The complete sentence version buries this element in the middle, rather than calling it out more explicitly.

Consider a Subtitle

Many authors follow the title: subtitle format in which the main title summarizes the thesis of the paper, then the subtitle explains why the paper is significant or clarifies the paper’s format.

Take for example: “Stromatolitic Knobs in Storrs Lake, San Salvador, Bahamas: Insights into Organomineralization.” The main title describes the subject of the paper (stromatolites in a particular field site). The subtitle after the colon describes why this subject is significant (the stromatolites can reveal information about organomineralization).

Another example is: “A New Strategy for Heavy Metal Polluted Environments: A Review of Microbial Biosorbents.” As in the previous example, the main title describes the subject of the paper, but in this case, the subtitle describes the format of the paper. The subtitle lets the reader know that instead of describing a single study on the remediation of heavy metal pollution, this paper will review the current body of knowledge (or at least several case studies) relating to microbial biosorbents pertaining to the main subject of heavy metal pollution remediation.

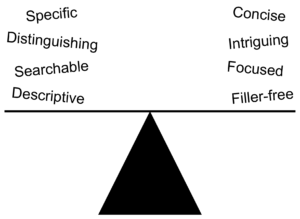

Strike a Balance

Whatever format you choose, the title should be relevant, descriptive, clear, and concise. A little creativity is always appreciated too, but remember that this is an academic paper. Creativity can help boost readership, but the objective is to use a title that clearly dictates the true purpose of the research. My professor’s facetious suggestion that I call my undergraduate thesis on corals, “Reefer Madness” was creative and semi-relevant, but I probably wouldn’t have been able to go on to publish it, (not to mention the copyright infringement). People tend to be a bit more whimsical with conference presentation titles, but it’s still more important to inform than to entertain.

The real key to a good title is to find a balance. Provide enough information to tell the reader what the paper is about, why it’s important, and what distinguishes it from other papers, but maintain enough brevity to intrigue, rather than overwhelm the reader.

Example Exercise

Imagine you are choosing a title for this paper: Si and Yair, 2019.

You want the title to focus on the main thesis of the research, which can be summarized by this quote from the abstract: “Our work highlights a mechanism whereby, in addition to deep-sea dissolution, changes in marine calcification acted to modulate carbonate compensation in response to reduced weathering linked to the late Neogene cooling and decline in atmospheric partial pressure of carbon dioxide.” The first part of the sentence is introductory, and doesn’t need to be in the title. Since the deep-sea dissolution is secondary to the primary thesis, that can also be left out.

You come up with this title: “Changes in marine calcification acted to modulate carbonate compensation in response to reduced weathering linked to cooling and a decline in atmospheric partial pressure of carbon dioxide during the late Neogene.” This title makes good use of key words and focuses on the primary thesis of the paper. However, it is very long (a total of 31 words)!

To reduce the word count, you think about how you can narrow the focus a bit more to reflect only the most important points of the thesis. You realize that reduced weathering is more directly linked to the decline in atmospheric carbon dioxide than to cooling, so cooling can be removed. “Partial pressure” is really just the means of measuring the carbon dioxide level, so that can also be removed.

This leaves you with: “Changes in marine calcification acted to modulate carbonate compensation in response to reduced weathering linked to a decline in atmospheric carbon dioxide during the late Neogene.”

Next, you think about how you can be more specific to help clarify your title. Instead of “changes” you can say, “reduced” to reflect how marine calcification changed. You add “continental” to specify the type of crust being weathered. Now you have: “Reduced marine calcification acted to modulate carbonate compensation in response to reduced continental weathering linked to a decline in atmospheric carbon dioxide during the late Neogene.”

You want the title to reflect what sets the research apart from previous work. Unlike in previous studies, this work did not take the approach of reconstructing the paleo-carbonate compensation depth. These are key words people would use to search for the previous research, not the approach this research took. Therefore, you remove the mention of carbonate compensation from the title.

Your new title is: “Marine calcification was reduced in response to reduced continental weathering linked to a decline in atmospheric carbon dioxide during the late Neogene.” This title is much more focused, but still uses key words. It’s still a bit long, though, at 22 words. By using descriptive phrasing instead of a complete sentence, you can reduce a lot of filler words like “a,” “to,” “the,” and “during.” Since marine calcification and continental weathering were both reduced, you can also rearrange the words and avoid redundancy by only using “reduced” once. Since CO2 is also a widely known abbreviation, you decide it is reasonable to make an exception to the “no abbreviations in the title” rule.

The final title of the paper is: “Reduced continental weathering and marine calcification linked to late Neogene decline in atmospheric CO2.” This title is only 14 words (two fewer than the recommended limit of 16), includes plenty of key words, and is specifically focused on the primary thesis of the paper.

Edit, Edit, Edit

The easiest way to choose a title is to go through the type of thought process used in the example exercise above. Start by simply writing a short summary of the main take-away of your research. Don’t worry about coming up with the perfect title right away. Once you have a good summary, then think about how you can narrow the focus, be more specific, and reduce filler words. Be ruthless in your editing, and eventually, you’ll have the perfect title (or at least, one that you and your coauthors can agree on).

If you need help improving your own scientific writing, be sure to check out Blue Dot Writing’s Scientific Manuscript Editing services, and check back with us next week for the next installment of our Anatomy of a Scientific Paper series.

Further Reading:

Knight, K. L., & Ingersoll, C. D. (1996). Structure of a scholarly manuscript: 66 tips for what goes where. Journal of athletic training, 31(3), 201. Retrieved August 14, 2019 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1318504/pdf/jathtrain00019-0011.pdf

“4 Important Tips on Writing a Research Paper Title” from Enago Academy